Poor sharks. They have a bad reputation, but are they really dangerous? After all, you're more likely to be killed by a cow than a shark [source: Faletto]. But nobody is making movies about deadly cownados. And while you're in the water, you're more apt to drown or be injured by your own surfboard than by a shark [source: Martin].

Researchers love to throw around statistics like these to redeem sharks. Here's another juicy one. In 2021, there were 17,989 instances of dogs biting humans, according the Insurance Information Institute [source: III]. That same year, there were just 47 unprovoked shark attacks off the U.S. coast [source: ISAF]. That means you're about 383 times more likely to be bitten by man's best friend than you are by a shark.

Still, even the possibility of a shark attack terrifies us, thanks to movies like "Jaws" and sensational news reports. For many, sharks represent the unknown and the unknowable. While we can forgive some of those nearly 18,000 dogs for biting us, sharks don't show the same types of emotion, which makes it easy to paint them as mindless man-eaters.

Sometimes the statistics support our fears. In the past few years, the number of shark attacks has risen slightly, although that's likely due to more people engaging in recreational water activities, as opposed to hungrier sharks.

Any shark that measures more than 6 feet (1.8 meters) is a potential threat to humans because it's big and because it likely has adaptations, such as more developed jaws and stronger teeth that have enabled its large size [sources: Burgess, Ritter]. These sharks may not be specifically trolling for human flesh, but if they were to take a sample bite, they could do some serious damage.

While the most dangerous shark may always be the one that's swimming right toward you, it's worth remembering that of the almost 400 identified shark species, less than 10 percent have been implicated in an attack on a human [source: Martin].

Of the approximately 30 species that have attacked, which are the most dangerous? Let's sift through the attack statistics, the stereotypes and the sharp teeth to find out. These 10 top the International Shark Attack File (ISAF) records of attacks around the world between 1580 and the present [source: ISAF]. Let's start with No. 10.

10: Blue Shark

Here's the good news: You don't have to worry about a blue shark (Prionace glauca) stalking you while you frolic in the waves a few yards from your beach blanket. This aquatic predator, which can grow more than 12 feet (3.6 meters) in length, prefers to remain in waters at least 1,150 feet (350 meters) deep. That's where it finds its dinner: small bony fishes, like herring and sardines, and invertebrates, like squid, cuttlefish and octopus. It's also been known to scavenge on dead marine animals and steal from fishermen's nets.

And that brings us to the bad news: Although blue sharks aren't known to be particularly aggressive — especially compared to their nastier cousins the bull sharks — they won't turn their noses up at a potential meal of human flesh, either, if you happen to be shipwrecked or floating on your seat cushion after surviving a plane crash.

Reportedly, blue sharks have circled unfortunates bobbing around in their feeding grounds, and have been known to take exploratory bites [source: Florida Museum of Natural History]. Blue sharks have been responsible for 13 unprovoked attacks worldwide, including four that resulted in deaths [source: ISAF].

In reality, blue sharks have far more to fear from people. An estimated 10 to 20 million of them are killed by humans each year. Many blue sharks are killed when they become entangled in fishermen's nets and others are slaughtered for their fins, which are sold on Asian markets for making shark fin soup, a delicacy [source: Florida Museum of Natural History].

9: Bronze Whaler

The bronze whaler (Carcharhinus brachyurus) gets its name from its gray to olive-green coloring [source: ISAF]. Bronze whalers are big, with males maturing at about 6.6 to 7.5 feet (2 to 2.3 meters) in length, while females mature at 7.9 feet (2.4 meters). Bronze whalers have distinctive outwardly hooked teeth, moderately rounded broad snouts, and bulges at the base of the upper caudal fin [source: Shark Research Institute].

They live in temperate waters around the world, but are distributed unevenly in populations that have little exchange between them. The bronze whaler is an important commercial catch for human consumption in New Zealand, Australia, Brazil and South Africa, where they're caught in bottom trawls, by line gear and by sport fishermen. The bronze whaler shark has been implicated in 15 shark attacks since 1962, only one of which resulted in a fatality [source: ISAF].

Bronze whalers often are seen close to the shore, feeding on schooling fish — sometimes in the surf, which potentially can bring them into proximity to humans. They're seasonally migratory for at least part of their range, and along the southern coast of Africa, they tend to follow large groups of migrating sardines. They're active, fast-moving creatures with the ability to leap out of the water [source: Shark Research Institute].

8: Oceanic Whitetip Shark

The oceanic whitetip (Carcharhinus longimanus) may only have 12 unprovoked attacks and three fatalities on the books, but that's because it might be getting away with many of its crimes by not leaving any evidence [source: ISAF]. Marine explorer Jacques Cousteau ranked the whitetip shark as one of the most dangerous for its brazenness in evaluating prey.

Found in deep waters, this shark became a primary enemy during times of war, when soldiers ended up in the water after their transport was attacked. Known for being the first on the scene of a shipwreck, this shark likely gobbled up many servicemen not reflected in the statistics. Most notably, the whitetip is thought to be responsible for eating many of the men aboard the Nova Scotia, which sunk in World War II and suffered more than 800 casualties [source: Levine].

The whitetip is probably one of the most abundant large fish in the ocean. Divers who encounter the fish report that this is a shark with attitude and boldness, unperturbed by the divers' defense mechanisms. It persistently and aggressively investigates divers.

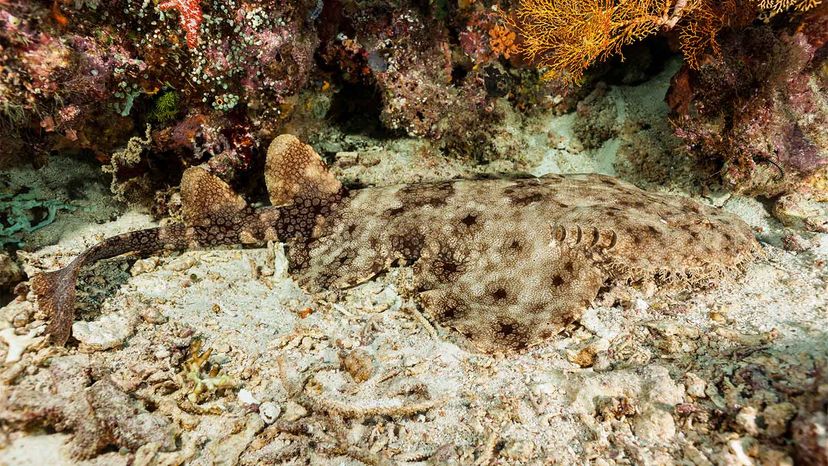

7: Wobbegong Shark

Wobbegong sharks — a name that's a catchword for multiple species of sharks in the genus Orectolobus — get their name from an Australian aboriginal word that means "shaggy beard." They're also known as carpet sharks, due to the ornate patterns on their bodies. Wobbegongs lie in wait on the ocean floor for crustaceans and fish to swim by [source: Smithsonian Ocean].

While wobbegongs may not look that ferocious, they're responsible for at least 19 attacks on humans, though they've yet to inflict a documented fatality [source: ISAF]. One species, the spotted wobbegong (Orectolobus maculatus), reportedly can be aggressive toward humans, with at least four documented attacks. There are accounts of unprovoked attacks on divers, as well as incidents in which wobbegongs bit people who stepped on them or let their limbs get too close to the mouth of the sharks, which may have mistook them for prey [source: Florida Museum].

Once a wobbegong latches onto a person, they're stubborn about letting go, which can lead to severe lacerations [source: Florida Museum].

Even so, wobbegongs are more in danger from humans than vice versa. They're often caught by trawlers and in lobster pots, and spearfishermen often kill them as well [source: Florida Museum].

6: Sand Tiger Shark

Researchers who've observed sand tiger sharks say they generally aren't aggressive toward humans unless provoked, but that's not much consolation if you're a fisherman and find yourself confronted with the predator's prominent, jagged-looking teeth [source: Florida Museum of Natural History]. Sand tigers have attacked humans 36 times, though, miraculously, none of the attacks proved fatal [source: ISAF].

The species (Carcharias Taurus) is found in most warm seas throughout the world, except for the eastern Pacific. In the western Atlantic Ocean, sand tiger sharks range from the Gulf of Maine to Argentina, and are commonly found in Cape Cod and Delaware Bay during the summer months. They're most often found close to shore, at depths ranging from 6 to 626 feet (1.8 to 190 meters), but are also found in shallow bays, coral and rocky reefs, and sometimes also in deeper areas around the outer continental shelves.

Sand tiger sharks are large and bulky, with flattened conical snouts and long mouths that extend behind the eyes; they sometimes have dark reddish or brown spots scattered on their bodies. Females can reach a maximum length of more than 10 feet (3 meters); males are usually just under 10 feet.

As previously mentioned, sand tigers have a hearty appetite for herring, mullets and rays, among other things, and they sometimes hunt in schools and cooperate by surrounding and bunching their prey. Sand tigers are fished for food in the north Pacific, northern Indian Ocean and tropical west coast of Africa. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies sand tigers as a "vulnerable" species [source: Florida Museum of Natural History].

5: Blacktip Shark

If you're a Florida surfer, you may already be familiar with the blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus), since the species reportedly inflicts 16 percent of the shark bites on surfing enthusiasts in your state. Blacktips also have chomped on humans along other parts of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States, and off the waters of South Africa and the Caribbean.

If there's an upside to this, it's that the species, which prefers depths of around 10 feet (3 meters), only averages about 5 feet (1.5 meters) in length and just 40 pounds (18 kilograms) in weight, and seldom inflicts anything more than a minor wound [source: Florida Museum of Natural History]. To date there've been 41 documented attacks on humans by blacktip sharks, with no fatalities [source: ISAF].

Though blacktips usually prefer saltwater, they also are often seen near shore around river mouths, bays, mangrove swamps and in other estuaries. They get their name from the distinctive black markings on the tips of their fins. They have stout bodies with a moderately long, pointed snouts and high, pointed first dorsal fins. They're dark gray-blue or brown on their upper bodies, with white underbellies and a distinctive white band across their flanks.

Blacktips feed primarily on small schooling fishes like herring and sardines, but they also eat bigger bony fish like catfish and grouper and have been known to make a meal out of some types of small sharks, stingrays, crustaceans and squids.

We'd be remiss if we didn't add that like many other shark species, blacktips have more to fear from humans than the other way around. They're caught by fishermen, who sell their meat for human consumption or to be used as fish meal to feed animals. Their fins are also sold in Asian markets for making soup. The IUCN classifies blacktips as "near threatened" around the world and "vulnerable" in the Northwest Atlantic region [source: Florida Museum of Natural History].

4: Requiem Sharks

Requiem sharks actually are a family of 12 genera and approximately 50 species. They have a funereal-sounding name, and for spear fishermen, in particular, they can be a lethal menace. That's because fish skewered and struggling on a spear emit low frequency vibrations that requiems can detect with their highly sophisticated sensory organs. Once they've arrived in the vicinity of the catch and can smell blood, their aggressive instincts can take over.

That's not a good thing, if you happen to be in the water with them, because the strong-swimming, torpedo-shaped predators, who travel either solo or in groups, have big mouths filled with sharp, serrated teeth [source: Randall]. Various types of requiem sharks have attacked humans 68 times, with one fatal attack on record [source: ISAF].

What makes the sharks even more frightening is that a few of requiem species, such as the gray reef shark, have a distinctive threat posturing. The sharks will swim laterally, toss their heads in an exaggerated fashion, arch their backs with their pectoral fins held downward, and snap their jaws menacingly. If you see a shark doing that, it's best to move slowly away. Requiem species vary in size, but the biggest can exceed 24 feet (7.3 meters) in length, often making them the biggest bullies on the block [source: Beller].

If there's a silver lining to all this, it's that requiems are voracious eaters who normally dine on a lot of other creatures besides humans, including sharks and rays, squid, octopus, lobster, turtles, marine mammals and sea birds [source: Randall]. Large and fierce members of the requiem family, like the bull shark, are especially dangerous to humans. We'll get to that next.

3: Bull Shark

The bull shark's statistics are pretty impressive. With a total of 121 attacks, including 26 unprovoked fatal attacks, the bull shark has already earned its spot as one of the three most dangerous sharks [source: ISAF]. The bull shark is as aggressive as its name implies.

Technically, the tiger shark surpasses the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) in terms of numbers of attacks and fatalities. But many researchers think that the bull shark gets off easy in terms of statistics and may actually be responsible for many of the attacks pinned on tiger sharks and the great white.

The bull shark is dangerous simply because it's more likely to come into contact with humans than some of the other sharks on our list. It can live in both salt and freshwater, and the bull has been spotted in water so shallow that humans can walk around in it. What's more, bull sharks are fairly territorial about their homes, so a person out for a simple stroll could be agitating bull sharks without even knowing it.

2: Tiger Shark

Tiger sharks aren't looking to specifically eat humans, but then, they weren't specifically looking to eat lumps of coal, cans of paint, packs of cigarettes or Senegalese drums either. These items have all been found in the bellies of tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier), which are known for their ability to eat just about anything [source: Parker]. So while other sharks may just want a sample to find out if a person is edible, the tiger shark is less likely to let go once it's taken a bite.

If a tiger shark does decide to continue eating, you're in for an unpleasant experience, to say the least. Their jaws have elastic muscles, which allow them to swallow pieces of prey much larger than what might seem possible. And little can be done once you're in the grip of the tiger shark's razor-sharp teeth, which can chomp through anything. Many a crunchy sea turtle has fallen prey to those teeth despite a hard, protective shell.

Those teeth, which can puncture and rip apart prey in a matter of seconds, have been responsible for a total of 138 attacks, including 36 fatalities [source: ISAF].

Now on to the No. 1 shark on the list. If you've seen the movie "Jaws," you can probably guess what it is.

1: Great White

You don't become the subject of a movie like "Jaws" without being dangerous in real life as well. Indeed, the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) leads all other sharks in attacks on people and boats, as well as fatalities. Currently, the great white shark has been connected with a total of 354 total unprovoked shark attacks, including 57 fatalities [source: ISAF].

In 2001, "Jaws" author Peter Benchley claimed that he couldn't have written the book today knowing what he knows now about great white sharks [source: McCarthy]. The great white is just not the mindless killing machine that was depicted on the silver screen. This shark is extremely curious, though, and may bite humans to determine if they would make a good meal. They generally don't return for seconds, though, because humans simply aren't very good food. These sharks much prefer the fatty blubber of seals and sea lions.

While some scientists say that great whites mistake surfers on their boards for seals, it may just be a youthful mistake. Some researchers think those sharks are likely the juveniles of the species who are in the first stages of adding seals and sea lions to their diet.

Whether it's mistaken identity or not will certainly matter very little to the poor person who does get trapped in these infamous jaws. As for being a "taste bite," the great white takes a pretty big taste, as it's able to consume 20 to 30 pounds (9 to 14 kilograms) of flesh with each bite, with the force of each bite measuring over 4,000 PSI [source: Brown]. With one bite like that, a human could bleed to death or die from damage to internal organs.

Most swimmers needn't worry about running into a great white shark though; they usually stay in deep waters and are fairly rare. But that elusiveness serves to make them even more frightening to some.

Originally Published: Jun 5, 2008

Dangerous Shark FAQ

What is the most dangerous shark?

Bull sharks are one of the most dangerous sharks in the world. They're very similar to their more infamous relatives, tiger sharks and great whites, both of which are considered equally as dangerous.

Which shark has killed the most humans?

As of April 2021, the great white shark - the species portrayed in the film "Jaws" - is responsible for the highest number of unprovoked attacks with 333 total events including 52 fatalities. However, it's important to note that the risk of being bitten or killed by a shark remains extremely low.

Do hammerhead sharks attack people?

Hammerhead sharks rarely ever attack human beings. In fact, humans are more of a threat to the species than the other way around. Only 16 attacks (with no fatalities) have ever been recorded globally.

Which is more dangerous: tiger sharks or bull sharks?

Unprovoked attacks by tiger sharks slightly exceed those of bull sharks. As of April 2021, tiger sharks are responsible for 131 attacks, including 34 fatalities while bull sharks have attacked 117 times resulting in 25 fatalities. However, it's worth noting that humans have a higher probability of coming into contact with a bull shark compared to other species because they tend to swim in the same areas as humans - shallow water.

Is it safe to swim with tiger sharks?

Most experienced divers agree that seeing a shark on a dive is a treat. Still, practicing safe behavior around them helps ensure a positive experience. The risk of harm from a shark encounter is statistically pretty small, but they are apex predators and should be treated with respect.

Lots More Information

Related Articles

- Why Do People Collect Shark Teeth?

- How Shark Attacks Work

- How Diving With Sharks Work

Sources

- Allen, Thomas B. "Shark Attacks: Their Causes and Avoidance." The Lyons Press. 2001.

- Bester, Cathleen. "Oceanic Whitetip Shark." Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. (May 20, 2022) https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/carcharhinus-longimanus/

- Braun, David. "Underwater Photographer On Swimming With Sharks." National Geographic News. March 8, 2005. (May 20, 2022)

- Bright, Michael. "The Private Life of Sharks: The Truth Behind the Myth." Stackpole Books. 1999.

- Burgess, G.H. "Shark Attacks in Perspective." International Shark Attack File. (May 20, 2022) http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/attacks/perspect.htm

- Castro, Jose L. and Peebles, Diane Rome. "The Sharks of North America." Oxford University Press. 2011. (May 20, 2022) http://books.google.com/books?id=KQdeVX1yX6AC&pg=PA406&dq=copper+shark+attack&hl=en&ei=8ynVTojHIsnX0QHrlemgAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CEUQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=copper%20shark%20attack&f=false

- Christian Science Monitor. "Great White Shark Population Lower Than Previously Believed." March 11, 2011. (Nov. 21, 2011) http://www.csmonitor.com/Environment/Wildlife/2011/0311/Great-white-shark-population-lower-than-previously-believed

- Compagno, Leonard J.V. "FAO species catalogue. Volume 4. Sharks of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of sharks species known to date. Part 2. Carcharhiniformes." Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1984. (May 20, 2022) https://www.fao.org/3/ad123e/ad123e00.htm

- Dehart, Andy. Personal Correspondence. July 18, 2008.

- Dell'Amore, Christine. "Biggest Great White Shark Caught, Released." National Geographic News. May 6, 2011. (May 20, 2022) https://web.archive.org/web/20110509063931/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2011/05/110506-biggest-great-white-sharks-apache-caught-animals-science/

- Dingerkus, Guido. "The Shark Watchers' Guide." Wanderer Books. 1985.

- Grace, Mark. "Field Guide to Requiem Sharks (Elasmobranchiomorphi: Carcharhinidae) of the Western North Atlantic." November 2001. (May 20, 2022) https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/legacy-pdfs/tr153.pdf

- Florida Museum of Natural History. "A Comparison of Shark Attack Fatalities with Dog Attack Fatalities in the U.S.: 2001-2010." Feb. 10, 2011. (May 20, 2022) http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/attacks/relariskdog.htm

- Florida Museum of Natural History. "Blacktip shark." (May 20, 2022) https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/carcharhinus-limbatus/

- Florida Museum of Natural History. "Blue Shark." (May 20, 2022) https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/prionace-glauca/

- Florida Museum of Natural History. "Bull Shark." (May 20, 2022) https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/carcharhinus-leucas/

- Florida Museum of Natural History. "Great Hammerhead." (Nov. 21, 2011) https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/sphyrna-mokarran/

- Florida Museum of Natural History. "Orectolobus maculatus." (May 20, 2022) https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/orectolobus-maculatus/

- Florida Museum of Natural History. "Sand tiger shark." (May 20, 2022) https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/carcharias-taurus/

- Florida Museum of Natural History. "Tiger shark." (May 20, 2022) https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/galeocerdo-cuvier/

- Florida Museum of Natural History. "White shark." (May 20, 2022) https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/carcharodon-carcharias/

- Insurance Information Institute. III.org. "Spotlight on: Dog bite liability." March 29, 2022. (May 20, 2022) https://www.iii.org/article/spotlight-on-dog-bite-liability

- International Shark Attack File. Floridamuseum.ufl.edu. "U.S. Shark Injuries vs. Bite Injuries in NYC" (May 20, 2022) http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/attacks/relariskcity.htm

- International Shark Attack File. Floridamuseum.ufl.edu. "ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark." Jan. 29, 2008. (May 20, 2022) http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/statistics/species2.htm

- International Shark Attack File. Floridamuseum.ufl.edu. "Bronze Whaler Shark: Carcharhinus brachyurus." (May 20, 2022) https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/carcharhinus-brachyurus/

- International Shark Attack File. (May 20, 2022) http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/Sharks/ISAF/ISAF.htm

- International Shark Attack File. Floridamuseum.ufl.edu. "ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark." (May 20, 2022) http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/Sharks/Statistics/species2.htm

- Lineaweaver, Thomas H. and Richard H. Backus. "The Natural History of Sharks." Nick Lyons Books/Schocken Books. 1984.

- Lloyd, Robin. "Shark attacks aren't the story, experts say." Live Science. Feb. 27, 2008. (May 20, 2022 ) https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna23376259

- Marinebio.org. "Blue Sharks, Prionace glauca." 1998. (May 20, 2022) https://www.marinebio.org/species/blue-sharks/prionace-glauca/

- Martin, R. Aidan. "What's Up With All These Shark Attacks?" ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. May 20 2022 http://www.elasmo-research.org/education/topics/saf_attacks.htm

- Monterey Bay Aquarium. "Oceanic Whitetip Shark Exhibit." (May 20, 2022) https://www.zoochat.com/community/threads/oceanic-whitetip-shark-exhibit.467458/

- National Geographic Wild. "Hammerhead shark." (Nov. 21, 2011) http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/hammerhead-shark/

- Parker, Steve and Jane. "The Encyclopedia of Sharks." Firefly Books. 2002.

- Raffaele, Paul. "Forget Jaws, Now it's ...Brains!" Smithsonian. June 2008. (May 20, 2022) https://web.archive.org/web/20080603015155/http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/great-white-sharks.html

- Randall, John E. "Coastal Fishes of Oman." University of Hawaii Press. 1995 (Nov. 21, 2022) http://books.google.com/books?id=TnWYDUE1ibkC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Ritter, Erich K. "Anatomy of a Shark Attack." Shark Info. 1999. (May 20, 2022) http://www.sharkinfo.ch/SI4_99e/accidents.html

- Ritter, Erich K. "Which shark species are really dangerous?" Shark Info. 1999. (May 20, 2022) http://www.sharkinfo.ch/SI1_99e/attacks2.html

- Shark Research Institute. "Bronze whaler shark – Carcharhinus brachyurus. " Sharks.org. (May 20, 2022) https://www.sharks.org/bronze-whaler-shark-carcharhinus-brachyurus

- Shark Research Committee. "Shark/Human Interactions Along the Pacific Coast of North America." (May 20, 2022) http://www.sharkresearchcommittee.com/interactions.htm

- Tennesen, Michael. "A Killer Gets Some Respect." National Wildlife. August/September 2000.

- Walker, Matt. "Are unprovoked shark attacks becoming more common?" BBC Nature. Aug. 17, 2011. (May 20, 2022) https://web.archive.org/web/20110825015650/http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/14559836

thententonarmstead.blogspot.com

Source: https://animals.howstuffworks.com/fish/sharks/most-dangerous-shark.htm

Komentar

Posting Komentar